The digital world is a vast ocean of data. LinkedIn, with its treasure trove of professional information, is a goldmine of insights waiting to be unearthed. But while the platform is a prime target for data scraping, scraping LinkedIn data raises several legal and ethical questions. This post explores what constitutes scraping and whether LinkedIn can ban you from its platform for such activities.

What Counts as Data Scraping?

Data scraping is the process of extracting large amounts of data from websites.

Here’s a simple example. Let’s say you want a list of all the books and their prices from an online bookstore. It would be very time-consuming to visit each book’s page manually, write down the price, and then move on to the next one. A scraper can automatically visit these pages and extract the relevant information to save time.

However, not all websites allow their data to be scraped, and some have explicit terms of service prohibiting scraping. It’s crucial to understand and respect these guidelines before attempting data scraping.

Bad Scraping versus Good Scraping

Data scraping, like any other tool, can be used for both ethical and unethical purposes.

Bad Scraping

Poor and malicious scraping practices include:

- Scraping sensitive data such as personal information, login credentials, or financial details

- Scraping information such as email addresses for spamming purposes

Good Scraping

Good scraping practices, on the other hand, include:

- Scraping data that is publicly available and does not infringe on personal privacy and rights

- Limiting the request rate to the website serve; avoid overloading or disrupting the website server they’re scraping

- Responsible handling, storage, and use of scraped data

- Using scraped data for ethical purposes, such as market research and data-driven decision-making

Understanding LinkedIn’s Stance on Data Scraping

Data scraping, in its essence, is not illegal. However, LinkedIn’s position is that unauthorized scraping violates its Terms of Service and is thus not allowed on its platform.

While scraping LinkedIn can yield valuable insights for businesses and marketers, it’s crucial to do so responsibly. Remember, LinkedIn has mechanisms in place to detect unauthorized scraping activities. Excessive browsing of profiles in a short period, for instance, may set off LinkedIn’s alarm bells.

The Legal Landscape

LinkedIn’s Terms of Service explicitly forbid the use of automation to gather data from their platform, including scraping, crawling, data mining, and so on.

But, is it breaking the law?

No, not exactly.

Legally, utilising automation tools and web scrapers on LinkedIn isn’t deemed illegal. The intricacies, however, lie in the nuances of scraping methods.

The Case of LinkedIn v. hiQ - A Timeline

2017 – LinkedIn takes legal steps to halt hiQ’s data scraping activities and issues a cease-and-desist letter. In response, hiQ pursues legal action against LinkedIn, successfully preventing them from stopping the scraping through a legal injunction.

2019 – LinkedIn appeals the decision to the higher Ninth Circuit Court, which upheld hiQ’s rights, reinforcing the legality of scraping publicly available data.

2021 – The legal tussle escalates to the Supreme Court. They grant LinkedIn’s plea to overturn the Ninth Circuit’s ruling, nullifying prior decisions and remanding the case back to the Ninth Circuit.

April 2022 – Despite the Supreme Court’s action, the Ninth Circuit reaffirmed hiQ’s original injunction against LinkedIn, essentially reverting the situation to its initial state.

November 2022 – The Court sides with LinkedIn, stating that hiQ breached LinkedIn’s User Agreement on data scraping by creating fake accounts and illicitly acquiring user data.

What does it all mean?

At the core of this legal tangle was LinkedIn’s accusation against hiQ Labs for scraping user profiles en masse, supposedly violating terms of service, hacking regulations, and breaching the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA).

The initial ruling in 2019 by the Ninth Circuit debunked LinkedIn’s claim under the CFAA, stating that scraping publicly accessible data didn’t breach the Act.

In April 2022, the Ninth Circuit reiterated this stance, emphasising that scraping such data isn’t a violation of the CFAA as defined by U.S. law.

While the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act was pivotal in this case, the Court didn’t explicitly declare web scraping of publicly available data as prohibited under the CFAA.

Instead, it pinpointed hiQ’s continuous scraping post the cease-and-desist letter and their creation of fake accounts as breaches.

In essence, data scraping remains lawful as long as it doesn’t encroach upon another’s domain or trigger actions against the scraper.

At the end of the day, prominent entities like Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg, and Google continue to employ web-scraping techniques effectively.

So, why can’t we?

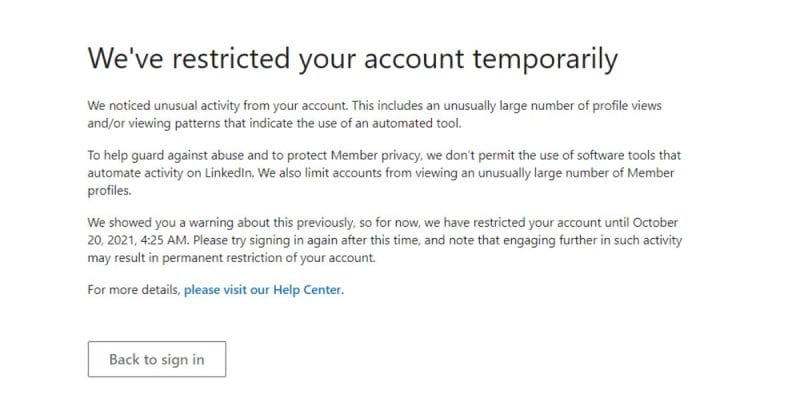

Can LinkedIn Ban You for Scraping?

The answer is yes.

While the aforementioned court ruling states that it’s legal to scrape publicly available data from LinkedIn, the platform itself does not allow it. If LinkedIn detects scraping activities, it can potentially result in your account being banned.

However, there are a myriad of reasons why many LinkedIn users are able to leverage data scraping without getting their accounts restricted or banned. Consider technologies like Dux-Soup and Phantombuster – they help users automate their LinkedIn activities, including data scraping. Yet, LinkedIn hasn’t taken these companies to court, like hiQ Labs.

Why is that?

Dux-Soup and Phantombuster, among many others, operate in a gray area. They extract data from LinkedIn profiles in a manner that mimics human behavior, which makes detection more challenging for LinkedIn’s anti-scraping mechanisms.

While users aren’t entirely safe from being detected and subsequently banned, adhering to the best practices of using such tools can significantly reduce the risk.

Here are some best practices:

- Set delays between actions: LinkedIn can detect automation if there are repeated actions without any delay. Realistic delays make the actions more human than machine.

- Limit your scraping activity: Similar to any platform, excessive activity on LinkedIn that falls outside the norm can raise suspicions. This includes viewing a large volume of profiles in a short period. To stay under the radar, limit scraping to 50 profiles per day.

Conclusion

Suffice to say, data scraping is a practice that has been around for a while now, and no platform, including LinkedIn, is immune to it. Data scraping has proven valuable for many businesses and professionals by efficiently gathering and analyzing large volumes of data.

Despite the legal intricacies surrounding data scraping on LinkedIn, the evolving landscape offers positive insights. Courts have showcased a growing recognition of the legitimacy of responsibly accessing publicly available data through scraping methods.

The precedence set by legal cases demonstrates a shift toward acknowledging the legality of data scraping when conducted within established boundaries. This presents a hopeful scenario for businesses and individuals seeking to harness data for legitimate purposes.

While adherence to LinkedIn’s Terms of Service is crucial to avoid repercussions, the evolving legal stance offers encouragement for responsible use of automation and web scraping tools.

Embracing these tools with a conscientious approach, combined with respect for platform policies, enables users to navigate this space effectively and ethically.

Ultimately, the determination of the best course of action on LinkedIn – whether to embrace or avoid automation and web scraping tools – lies in the hands of the users.